"If there is no truth, there is no injustice." - Norman Geras

Now that I am 7 weeks into the MSW program at UH, I have a clear sense that field of social work is deeply concerned with social justice. This includes justice for marginalized groups like ethnic minorities, women, the elderly and those with disabilities just to name a few. Like all of the students and faculty I've met in the program so far, the concepts of diversity, empowerment and equal opportunity are values that I deeply believe in. In that sense, I am right where I belong: among people that want to see social change resulting in less discrimination and more cultural awareness, less stereotyping and more understanding, less scapegoating and more dialogue.

At the same time, it's suddenly strange to be completely removed from the surroundings of my conservative evangelical upbringing. Detached from this environment, I'm finding that I'm not as politically "liberal" as I once thought fancied myself. It's much more fun to play around with liberal/progressive/missional ideas when you can experiment safely within the theological boundaries of traditional Christian orthodoxy. I used to think that voting for pro-choice candidates and supporting hospital visitation rights for homosexual partners was the definition of "liberal" and I thought this made me some sort of evangelical rebel. In the social work profession, however, these are stale and commonplace opinions that don't impress anyone.

At the same time, it's suddenly strange to be completely removed from the surroundings of my conservative evangelical upbringing. Detached from this environment, I'm finding that I'm not as politically "liberal" as I once thought fancied myself. It's much more fun to play around with liberal/progressive/missional ideas when you can experiment safely within the theological boundaries of traditional Christian orthodoxy. I used to think that voting for pro-choice candidates and supporting hospital visitation rights for homosexual partners was the definition of "liberal" and I thought this made me some sort of evangelical rebel. In the social work profession, however, these are stale and commonplace opinions that don't impress anyone.

Over here (or "over there" depending on how you look at it), voting for Democrats and bashing organized religion are just par for the course. It's not enough to seek social change where it is needed; you almost have to deny that there are any areas where change is not needed, as if change for the sake of change were the guiding principle. It's not enough to explore the gray areas where abortion could sometimes be permissible; you have to decry any suggestion that it's ever NOT permissible or even a gray area to begin with. It's not enough just to acknowledge the historic injustices carried out in the name of religion, you also have to check your faith at the door, as if it will do nothing but hinder your efforts to make the world a better place. It's not enough to consider all points of view to determine what works best; you have to deny that a best way even exists. In the past, I'd heard what I thought were rumors and tall tales about the mythical netherworld where words like "faith," "truth" and "morality" were frowned-upon or taboo, but I never seriously considered engaging the cold reality of such places.

It would be unfair and irresponsible to lump an entire profession of 500,000+ people under a single label or stereotype, but I've noticed a general tendency that can be indifferent and sometimes hostile to the Christian faith. Many of my church friends would probably be shocked or offended by my class discussions, while the majority of my classmates would likely be genuinely outraged by the teachings of my church. I have no doubt that plenty of Christians are employed as social workers and I've met at least 3 other students in the program who would, like me, identify themselves that as evangelical Christians. However, there remains very little overlap between the evangelical political spectrum and the political framework of the social work academy. I am either a right-wing social worker or a left-wing evangelical. If church sometimes brings out my liberal side that looks for gray areas, social work school has brought out my conservative side that searches for black and white.

It would be unfair and irresponsible to lump an entire profession of 500,000+ people under a single label or stereotype, but I've noticed a general tendency that can be indifferent and sometimes hostile to the Christian faith. Many of my church friends would probably be shocked or offended by my class discussions, while the majority of my classmates would likely be genuinely outraged by the teachings of my church. I have no doubt that plenty of Christians are employed as social workers and I've met at least 3 other students in the program who would, like me, identify themselves that as evangelical Christians. However, there remains very little overlap between the evangelical political spectrum and the political framework of the social work academy. I am either a right-wing social worker or a left-wing evangelical. If church sometimes brings out my liberal side that looks for gray areas, social work school has brought out my conservative side that searches for black and white.

As I expressed in an earlier blog post, the worldview and motivation that drives my involvement in the social work vocation is my understanding of the Christian faith, which is built upon the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. What matters for the Christian is defined by what matters to God. Christ has set the example for us to follow. As I see it, social work is an important part of the greater Kingdom work of bringing heaven to earth. Charity, though necessary, cannot be an adequate substitute for justice. It is hypocrisy to sing worship songs on Sunday, only to leave the sanctuary and ignore the systemic inequalities that benefit the privileged at the expense of the poor and oppressed. As the prophet Amos cried on behalf of God, "Take away from Me the noise of your songs; I will not even listen to the sound of your harps. But let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream." (Amos 5:23-24, NASB)

As a Christian, I am comfortable with the vocabulary of faith and the concept of moral truth. Domestic violence is not just behaviorally destructive, it is morally wrong. Racism and sexism are not just politically incorrect; they are offenses against God. Child labor in sweatshops is not just disturbing and horrifying, it is immoral, sinful and just plain wrong. This is very obvious to me.

As a Christian, I am comfortable with the vocabulary of faith and the concept of moral truth. Domestic violence is not just behaviorally destructive, it is morally wrong. Racism and sexism are not just politically incorrect; they are offenses against God. Child labor in sweatshops is not just disturbing and horrifying, it is immoral, sinful and just plain wrong. This is very obvious to me.

I doubt that my secularist classmates and professors would mind me condemning these injustices in such strong moral terms, but the social work literature I've read so far (not unlike the writing of some postmodern Christians) seems to have a love-hate relationship with truth and certainty. Social work is absolutely certain that genocide, sexual abuse and environmental degradation are wrong, but they adamantly refrain from making any judgments on whether sexual fidelity in marriage is preferable to adultery or whether a two-parent household is more ideal for child development than a single-parent family. Caring for orphans, widows and battered women is a biblical mandate, to be sure, but it should not let us off the hook when it comes to promoting responsible parenting and healthy relationships.

Which brings me back to the moral and spiritual components of injustice. The exploitation of children through sweatshop labor is wrong not only because it assaults human dignity and violates ethical business practices, but also because those children have been fearfully and wonderfully created by God. They bear His image. They each have a soul. Their lives are sacred. They are loved their Creator and are beautiful in His sight. When they are abused and discarded, it is a moral issue of eternal significance. If anyone cares about these kinds of systemic injustices that are enabled by corruption, backroom political alliances, trade agreements and the unrestricted free market, it should be Christians. If we take Matthew 25 seriously, the "least of these" must be treated with the same awareness and respect that we reserve for the Almighty Christ.

"If there is no truth, there is no injustice."

"If there is no truth, there is no injustice."

The concept of justice hinges on truth. I first discovered Norman Geras' quote on the web page of Paul Adams, my faculty advisor. Dr. Adams lists this as one of his favorite quotes and it is quickly becoming one of mine as well. It's baffling to me how social work, a discipline whose core values are all about promoting social justice, fairness and the empowerment of oppressed groups, has such a frosty relationship with the idea of truth. I'll admit that as a lifelong churchgoer, I've sometimes witnessed a one-size-fits-all approach applied too broadly in areas that should be left subjective to the complexities of life. I understand the dangers of religious fundamentalism, of "other-izing" and denigrating those of dissenting viewpoints. Too often, the language of absolute truth has been misused and abused by the church.

But how do I know this is wrong? Because of truth! How can I even say that child abuse and neglect must be prevented in the first place? Because of truth! How can say with any authority that torture and genocide must be stopped? Because of truth! If there is no truth, who's to say that the weak should be defended or the oppressed lifted up? If there is no truth, on what basis can we argue that peacemaking through diplomatic dialogue is preferable to pre-emptive war and aggressive militarization?

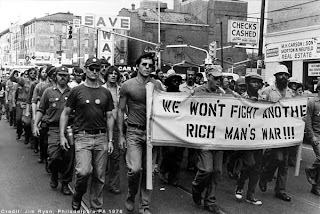

As Martin Luther King famously said, "the arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice." The basis of such justice is the concept of truth. King could not have spoken truth to power if he had allowed for racism and segregation to be right for some but wrong for others. His speeches consistently described injustice in moral and biblical terms. Those who have historically fought for the abolition of slavery, labor rights, women's rights and civil rights (many of them people of deep Christian faith) were not following some sort of vague and nebulous secular altruism. They spoke out because they were morally compelled to do so. The spiritual foundations of these movements are exactly what fueled the pursuit what is fair, just, honorable and true. If we shut out faith and truth from the conversation, we have lost one of our most powerful weapons in the fight against injustice. If there is no truth, there is no injustice.

It is my prayer that my own pursuit of justice will always be in service to the Way, the Truth and the Life.

October 9, 2008

On justice and truth

Labels:

evangelicalism,

faith,

justice,

philosophy,

politics,

social work,

theology

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

That is a great quote.

I am happy to know that like many great social activists in history, you base your quest on your "understanding of the Christian faith". My mom is also a social worker for the same reason.

Indeed, truth is important to justice.

Sadly, however, people often disagree on what the truth is. In today's world, truth is relative.

Even people with good intentions find themselves unable to bring lasting significant change to the world if they don't know the truth. They may help people in the short run in bits in pieces, but until they learn the truth revealed to us through Christ, the change that they bring to this world is like a tiny band-aid applied to a gigantic gunshot wound.

Post a Comment